Why India Needs To Buy Better Water Data From China

By Nilanjan Ghosh, Jayanta Bandyopadhyay, Sayanangshu Modak/ thethirdpole.net

China-India hydropolitical relations over the Brahmaputra have been a matter of great contention, embittered by the popular perception that Chinese interventions on the Yarlung Tsangpo (the name of the river in Tibet) can have deleterious impacts on India. This is best exemplified by the writings of Brahma Chellaney, both in his 2011 book, and in subsequent essays.

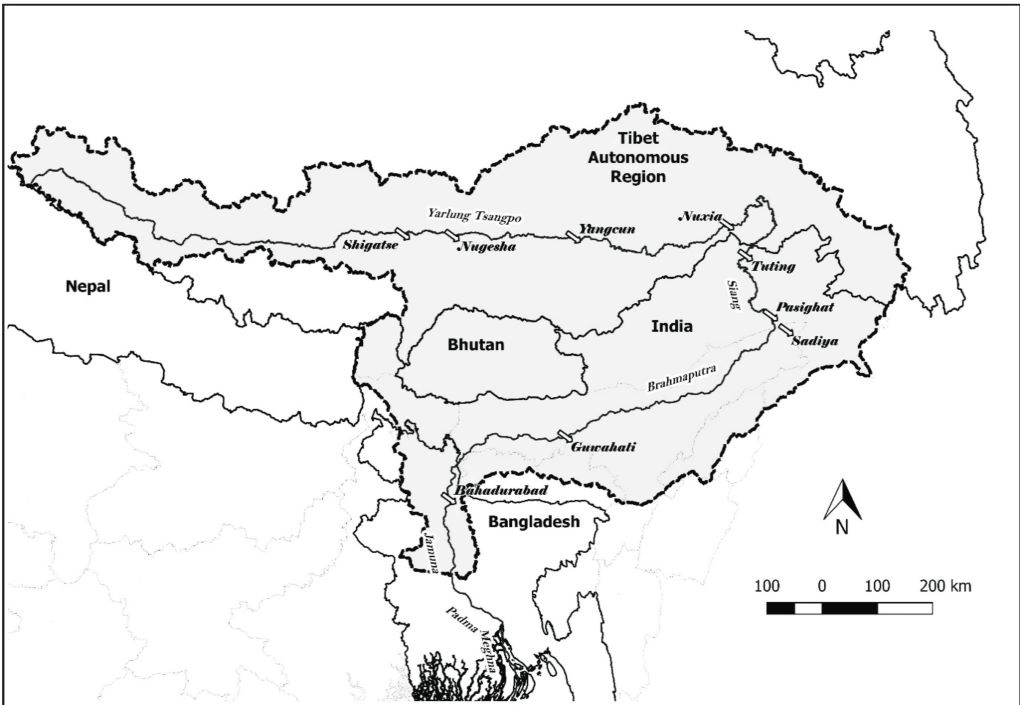

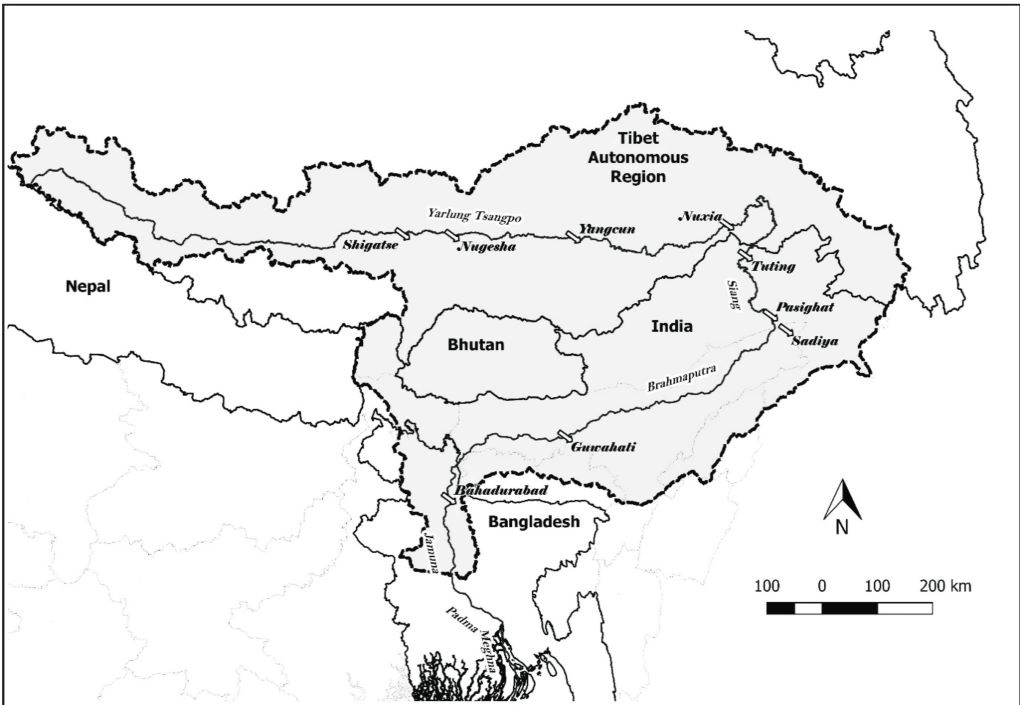

In our writings we have observed that the precipitation and flow levels in the northern Himalayan arc in the Chinese area (Tibetan Plateau) are marginal, thereby inferring that any intervention on the Yarlung Tsangpo will have potentially much less impact than perceived (See Bandyopadhyay et al 2016; Ghosh 2017; Ghosh et al 2019). There is also the silver lining – an existing Memorandum of Understanding (MoU), first signed in 2002, on the sharing of flow data on the Yarlung Tsangpo by China to India. This MoU had been renewed in 2008, 2013 and 2018 and is presently operational. The MoU is aimed at facilitating advance warning for flooding in India during monsoon. However, we argue here that the choice of measuring stations from which the flow data is shared is inadequate as it does not consider the areas endowed with greater rainfall, located in the southern Himalayas. The Brahmaputra, flowing through southern Tibet, northeast India, and eastern Bangladesh, and with tributaries in Bhutan, is 2,880 kilometres in length. Of that, 1,625 kilometres flows through the Tibetan plateau as the Yarlung Tsangpo; 918 kilometres flows in India as the Siang, Dihang, and Brahmaputra; and the 337 kilometres in Bangladesh (under the name of Jamuna) until it merges into the Padma near Goalando. The Brahmaputra is identified as the flow downstream of the meeting of three tributaries — namely, Luhit, Dibang, and Siang/Dihang, near Sadiya in Assam. This geographical distribution of length gives the impression that the Yarlung Tsangpo makes a substantial contribution to the total flow of the Brahmaputra, which is a myth. Yet, this myth has trigerred the perception that Chinese interventions upstream can deplete water downstream. Allegedly, it may also be responsible for the choice of measuring stations in the Tibetan boundary in the north aspect of the Himalayan arc as mentioned in the data-sharing MoU. [The Brahmaputra sub-basin; map prepared by authors]

The hydrological gauging stations in the MoU

The data sharing agreement identifies three hydrological gauging stations in Tibet for the purpose of developing an early-warning system – Nugesha, Yangcun and Nuxia. The MoU requires China to share data on rainfall, water level and discharge, primarily during the monsoon period (May 15 to October 15) when the chances of flooding are maximum. The agreement also ensures sharing of data in the non-flood season when the water levels at the designated stations are close to breaching the danger level. For its part, India is required to pay a mutually agreed sum of money for the data. It is also required to share information regarding data utilisation. The exchange works in conjunction with the establishment of an institutional mechanism, known as the India-China Expert Level Mechanism (ELM) on Transborder Rivers.

Despite the positive intentions of friendly cooperation, equality and mutual benefit, all of which are enshrined in the agreement, it seems that the primary purpose of designing an effective early-warning system is woefully lost. This is because all the three stations are located in the rain-shadow, in the north aspect of the Himalayas. A better understanding of the hydro-meteorology of the basin in general, and the region comprising the Great Bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo in particular, is necessary to improve the design of the agreement.

Understanding hydro-meteorological realities

The Brahmaputra is mostly fed by rainfall, with snow and glacial melt contributing barely 13% of the total flow of the stream as measured at Bahadurabad in northern Bangladesh. One needs to keep in mind that many of the tributaries of the Brahmaputra like Teesta, Manas, Luhit, Subansiri, and Dibang are also fed by glaciers and contribute to the total run-off of the main course. This implies that the glacial contribution to Brahmaputra’s flow by the Yarlung Tsangpo is even lower.

While precipitation is the largest contributor to the flow, rainfall is extremely varied across the basin. The Tibetan Plateau receives very little rainfall by virtue of its location on the north aspect of the Himalayan crestline. Comparatively, the rainfall in the part of the basin located in the south aspect of the crestline is much higher and the annual average precipitation (that includes mainly rainfall) may reach about 4,500 mm. This is in stark contrast to the average annual precipitation of about 300 mm in the trans-Himalaya, north of the crestline. All the three gauging stations from which India gets the hydrological data as part of the MoU are located north of the Himalayan crestline.

While much of the flow in the Yarlung Tsangpo that enters Arunachal Pradesh in India as Siang is generated in the south aspect of the Himalaya, there seems to be an absence of flow data in the stretch of the river from the crestline to the China-India border. In view of this gap, for all practical purposes, the MoU is inadequate in establishing a comprehensive early warning system downstream.

For Full Story, Click Here

[The Brahmaputra sub-basin; map prepared by authors]

The hydrological gauging stations in the MoU

The data sharing agreement identifies three hydrological gauging stations in Tibet for the purpose of developing an early-warning system – Nugesha, Yangcun and Nuxia. The MoU requires China to share data on rainfall, water level and discharge, primarily during the monsoon period (May 15 to October 15) when the chances of flooding are maximum. The agreement also ensures sharing of data in the non-flood season when the water levels at the designated stations are close to breaching the danger level. For its part, India is required to pay a mutually agreed sum of money for the data. It is also required to share information regarding data utilisation. The exchange works in conjunction with the establishment of an institutional mechanism, known as the India-China Expert Level Mechanism (ELM) on Transborder Rivers.

Despite the positive intentions of friendly cooperation, equality and mutual benefit, all of which are enshrined in the agreement, it seems that the primary purpose of designing an effective early-warning system is woefully lost. This is because all the three stations are located in the rain-shadow, in the north aspect of the Himalayas. A better understanding of the hydro-meteorology of the basin in general, and the region comprising the Great Bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo in particular, is necessary to improve the design of the agreement.

Understanding hydro-meteorological realities

The Brahmaputra is mostly fed by rainfall, with snow and glacial melt contributing barely 13% of the total flow of the stream as measured at Bahadurabad in northern Bangladesh. One needs to keep in mind that many of the tributaries of the Brahmaputra like Teesta, Manas, Luhit, Subansiri, and Dibang are also fed by glaciers and contribute to the total run-off of the main course. This implies that the glacial contribution to Brahmaputra’s flow by the Yarlung Tsangpo is even lower.

While precipitation is the largest contributor to the flow, rainfall is extremely varied across the basin. The Tibetan Plateau receives very little rainfall by virtue of its location on the north aspect of the Himalayan crestline. Comparatively, the rainfall in the part of the basin located in the south aspect of the crestline is much higher and the annual average precipitation (that includes mainly rainfall) may reach about 4,500 mm. This is in stark contrast to the average annual precipitation of about 300 mm in the trans-Himalaya, north of the crestline. All the three gauging stations from which India gets the hydrological data as part of the MoU are located north of the Himalayan crestline.

While much of the flow in the Yarlung Tsangpo that enters Arunachal Pradesh in India as Siang is generated in the south aspect of the Himalaya, there seems to be an absence of flow data in the stretch of the river from the crestline to the China-India border. In view of this gap, for all practical purposes, the MoU is inadequate in establishing a comprehensive early warning system downstream.

For Full Story, Click Here

Also Read:

In our writings we have observed that the precipitation and flow levels in the northern Himalayan arc in the Chinese area (Tibetan Plateau) are marginal, thereby inferring that any intervention on the Yarlung Tsangpo will have potentially much less impact than perceived (See Bandyopadhyay et al 2016; Ghosh 2017; Ghosh et al 2019). There is also the silver lining – an existing Memorandum of Understanding (MoU), first signed in 2002, on the sharing of flow data on the Yarlung Tsangpo by China to India. This MoU had been renewed in 2008, 2013 and 2018 and is presently operational. The MoU is aimed at facilitating advance warning for flooding in India during monsoon. However, we argue here that the choice of measuring stations from which the flow data is shared is inadequate as it does not consider the areas endowed with greater rainfall, located in the southern Himalayas. The Brahmaputra, flowing through southern Tibet, northeast India, and eastern Bangladesh, and with tributaries in Bhutan, is 2,880 kilometres in length. Of that, 1,625 kilometres flows through the Tibetan plateau as the Yarlung Tsangpo; 918 kilometres flows in India as the Siang, Dihang, and Brahmaputra; and the 337 kilometres in Bangladesh (under the name of Jamuna) until it merges into the Padma near Goalando. The Brahmaputra is identified as the flow downstream of the meeting of three tributaries — namely, Luhit, Dibang, and Siang/Dihang, near Sadiya in Assam. This geographical distribution of length gives the impression that the Yarlung Tsangpo makes a substantial contribution to the total flow of the Brahmaputra, which is a myth. Yet, this myth has trigerred the perception that Chinese interventions upstream can deplete water downstream. Allegedly, it may also be responsible for the choice of measuring stations in the Tibetan boundary in the north aspect of the Himalayan arc as mentioned in the data-sharing MoU.

[The Brahmaputra sub-basin; map prepared by authors]

The hydrological gauging stations in the MoU

The data sharing agreement identifies three hydrological gauging stations in Tibet for the purpose of developing an early-warning system – Nugesha, Yangcun and Nuxia. The MoU requires China to share data on rainfall, water level and discharge, primarily during the monsoon period (May 15 to October 15) when the chances of flooding are maximum. The agreement also ensures sharing of data in the non-flood season when the water levels at the designated stations are close to breaching the danger level. For its part, India is required to pay a mutually agreed sum of money for the data. It is also required to share information regarding data utilisation. The exchange works in conjunction with the establishment of an institutional mechanism, known as the India-China Expert Level Mechanism (ELM) on Transborder Rivers.

Despite the positive intentions of friendly cooperation, equality and mutual benefit, all of which are enshrined in the agreement, it seems that the primary purpose of designing an effective early-warning system is woefully lost. This is because all the three stations are located in the rain-shadow, in the north aspect of the Himalayas. A better understanding of the hydro-meteorology of the basin in general, and the region comprising the Great Bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo in particular, is necessary to improve the design of the agreement.

Understanding hydro-meteorological realities

The Brahmaputra is mostly fed by rainfall, with snow and glacial melt contributing barely 13% of the total flow of the stream as measured at Bahadurabad in northern Bangladesh. One needs to keep in mind that many of the tributaries of the Brahmaputra like Teesta, Manas, Luhit, Subansiri, and Dibang are also fed by glaciers and contribute to the total run-off of the main course. This implies that the glacial contribution to Brahmaputra’s flow by the Yarlung Tsangpo is even lower.

While precipitation is the largest contributor to the flow, rainfall is extremely varied across the basin. The Tibetan Plateau receives very little rainfall by virtue of its location on the north aspect of the Himalayan crestline. Comparatively, the rainfall in the part of the basin located in the south aspect of the crestline is much higher and the annual average precipitation (that includes mainly rainfall) may reach about 4,500 mm. This is in stark contrast to the average annual precipitation of about 300 mm in the trans-Himalaya, north of the crestline. All the three gauging stations from which India gets the hydrological data as part of the MoU are located north of the Himalayan crestline.

While much of the flow in the Yarlung Tsangpo that enters Arunachal Pradesh in India as Siang is generated in the south aspect of the Himalaya, there seems to be an absence of flow data in the stretch of the river from the crestline to the China-India border. In view of this gap, for all practical purposes, the MoU is inadequate in establishing a comprehensive early warning system downstream.

For Full Story, Click Here

[The Brahmaputra sub-basin; map prepared by authors]

The hydrological gauging stations in the MoU

The data sharing agreement identifies three hydrological gauging stations in Tibet for the purpose of developing an early-warning system – Nugesha, Yangcun and Nuxia. The MoU requires China to share data on rainfall, water level and discharge, primarily during the monsoon period (May 15 to October 15) when the chances of flooding are maximum. The agreement also ensures sharing of data in the non-flood season when the water levels at the designated stations are close to breaching the danger level. For its part, India is required to pay a mutually agreed sum of money for the data. It is also required to share information regarding data utilisation. The exchange works in conjunction with the establishment of an institutional mechanism, known as the India-China Expert Level Mechanism (ELM) on Transborder Rivers.

Despite the positive intentions of friendly cooperation, equality and mutual benefit, all of which are enshrined in the agreement, it seems that the primary purpose of designing an effective early-warning system is woefully lost. This is because all the three stations are located in the rain-shadow, in the north aspect of the Himalayas. A better understanding of the hydro-meteorology of the basin in general, and the region comprising the Great Bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo in particular, is necessary to improve the design of the agreement.

Understanding hydro-meteorological realities

The Brahmaputra is mostly fed by rainfall, with snow and glacial melt contributing barely 13% of the total flow of the stream as measured at Bahadurabad in northern Bangladesh. One needs to keep in mind that many of the tributaries of the Brahmaputra like Teesta, Manas, Luhit, Subansiri, and Dibang are also fed by glaciers and contribute to the total run-off of the main course. This implies that the glacial contribution to Brahmaputra’s flow by the Yarlung Tsangpo is even lower.

While precipitation is the largest contributor to the flow, rainfall is extremely varied across the basin. The Tibetan Plateau receives very little rainfall by virtue of its location on the north aspect of the Himalayan crestline. Comparatively, the rainfall in the part of the basin located in the south aspect of the crestline is much higher and the annual average precipitation (that includes mainly rainfall) may reach about 4,500 mm. This is in stark contrast to the average annual precipitation of about 300 mm in the trans-Himalaya, north of the crestline. All the three gauging stations from which India gets the hydrological data as part of the MoU are located north of the Himalayan crestline.

While much of the flow in the Yarlung Tsangpo that enters Arunachal Pradesh in India as Siang is generated in the south aspect of the Himalaya, there seems to be an absence of flow data in the stretch of the river from the crestline to the China-India border. In view of this gap, for all practical purposes, the MoU is inadequate in establishing a comprehensive early warning system downstream.

For Full Story, Click Here

Latest Videos